Plant Some Damn Flowers

Beautifying the city starts with improving the landscaping and green spaces.

The Ozark Mountains are full of dazzling natural resources. Remote trails, glistening waterways and vibrant foliage make southwest Missouri ideal for outdoor enthusiasts around the country. Unfortunately, Springfield’s urban center isn’t as spectacular. “There is quite a bit of the city that would benefit from beautification and corridor improvement,” says Mary Lilly Smith, director of planning and development for the City of Springfield. Fortunately, public beautification is currently top of mind at the City office. Late last year, the Department of Transportation selected Springfield to receive $20,960,822 for a game-changing project: the Grant Avenue Parkway, a heavily landscaped parkway that will connect center city attractions including Wonders of Wildlife (WOW) and the downtown area. The grant comes as part of the Department of Transportation’s $900 million Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) discretionary grants program.

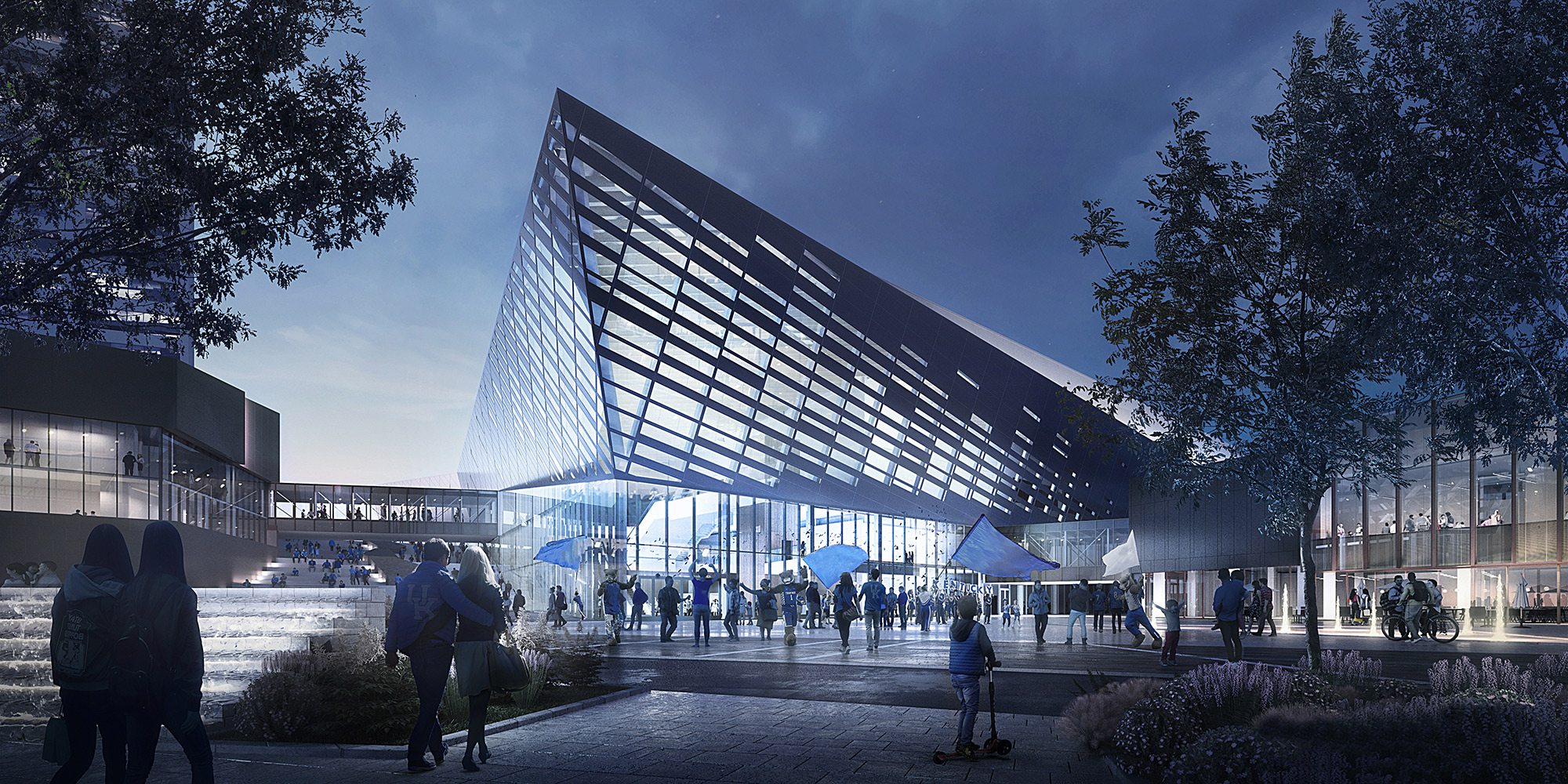

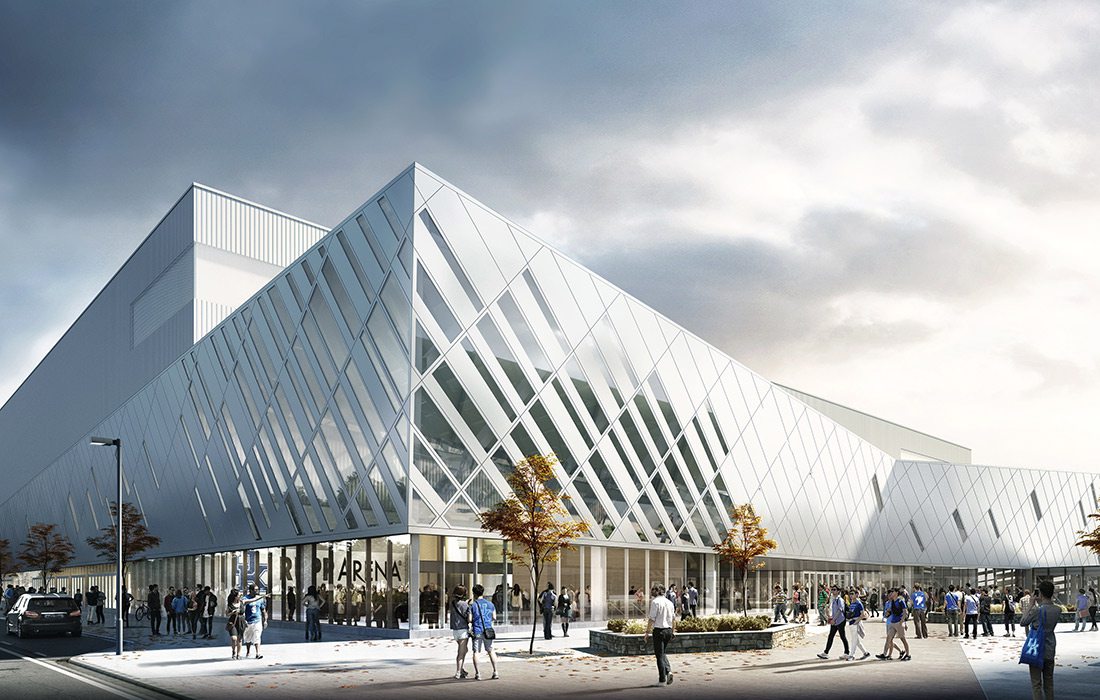

According to the City of Springfield’s website, the Grant Avenue Parkway will feature a roomy 10-foot wide pedestrian trail, an artistic bridge over Fassnight Creek and a scenic loop through the downtown area. Sarah Kerner, the City of Springfield’s economic development director, notes that the project will take several years to even begin construction—there’s still a lot of planning, design and property acquisition to do, not to mention public input sessions. Still, she has high hopes given the economic impact of WOW. The City reports that since opening in September 2017, the aquarium has resulted in significantly increased hotel nights and attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors. Connect WOW to downtown Springfield, where public and private investors have contributed half a billion dollars since 1996, and you have one extremely compelling parkway attraction for residents and visitors alike. “Sometimes I feel like Springfieldians can be too humble,” Kerner says. “We don’t want to demand too much. This is going to be a top-of-the-line attraction, and we deserve it.”

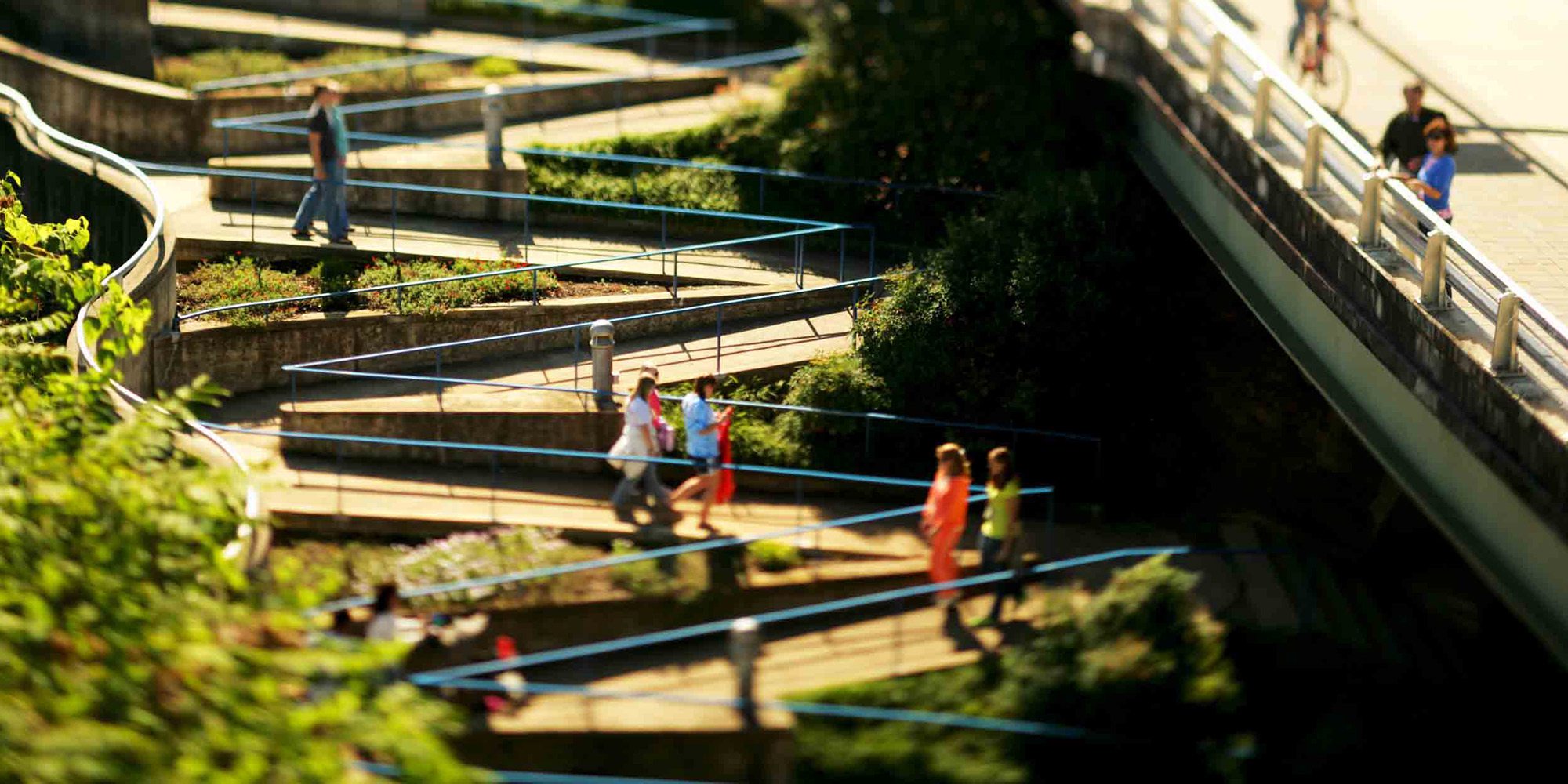

The Grant Avenue Parkway is a major step toward prioritizing public beautification in Springfield. It’s also a big win for the dreamers who draw inspiration from other communities like Lexington, Kentucky, known for stellar downtown landscaping punctuated by images of Big Lex, the official symbol of Lexington’s equestrian heritage. Another notable example is Chattanooga, Tennessee, known for its Riverwalk, a 13-mile stretch along the southern banks of the Tennessee River that connects popular attractions and urban neighborhoods. The Riverwalk puts public art to excellent use—including the Trail of Tears passageway filled with art by Cherokee artists. “These were things that told the story of our city,” says Kim White, executive director of Chattanooga’s nonprofit development engine, River City Company.