The Story of Hammons Black Walnuts

Four generations strong, the Hammons Black Walnuts family works with an organized buying network across 12 states to supply the American black walnut to tables across the world.

by Dori Grinder

Sep 2025

As the temperatures fall, so do the black walnuts from the trees scattered across the Ozarks. This is the time of year when the Hammons Black Walnuts family gears up for harvest—the same way they have for eight decades. It all starts with a black walnut falling to the ground, and someone picking it up and bringing it to a local hulling station. The harvesting of this wild crop spans thousands of people, across 12 states and 200 buying stations, all to arrive in Stockton, Missouri, at Hammons Black Walnuts—the pillars of the American black walnut industry.

To further invest in their community after a 2003 tornado wiped out the town square, the Hammons family created a retail space on the Stockton square hoping to spur economic revitalization. The Hammons Black Walnut Emporium features black walnuts, baked goods and cookbooks, a coffee shop and deli in addition carrying several different brands of black walnut ice cream available year-round by the scoop. While being firmly rooted in Stockton, Missouri, in the heart of the black walnut country, the reach of the black walnut business goes far beyond southwest Missouri.

The Early Days

As a business owner with a grocery store in the small town of Stockton, Ralph Hammons was accustomed to buying produce from local farmers and was always on the lookout for products that would interest his customers. At the time, he was buying shelled black walnuts from a company in Staunton, Virginia, to sell in his grocery store. After returning from the World War II, Ralph noticed the abundant number of black walnuts on the trees dotting the Missouri countryside and wondered if there was an opportunity with the wild nuts.

As it turns out, Ralph’s hunch was right.

Due to a low crop in Virginia that year, Hammons was able to secure a contract with a company there to receive the Missouri black walnut harvest for their own customers.

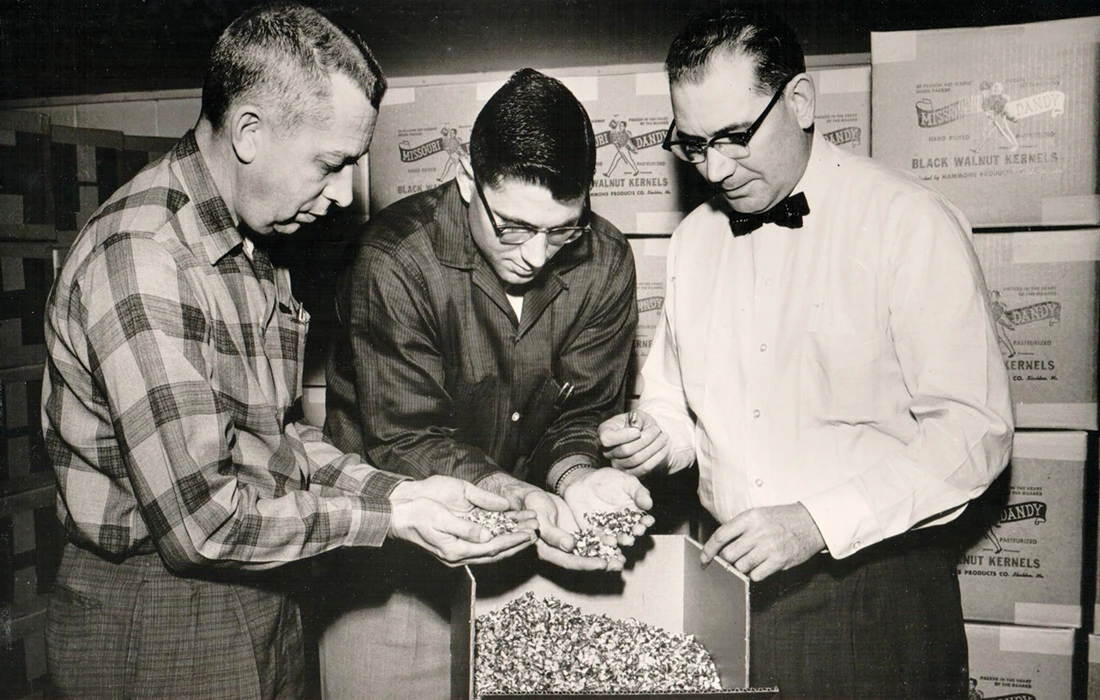

In 1945, Hammons’ first black walnut program was born with the purchase of three million pounds of black walnuts harvested by hand by hard-working southwest Missouri families that first year. Before shipping them to Virginia, Hammons and his team had work to do. “The nuts had to be hand-hulled, not through a hulling machine, because they didn’t have one then,” says Dwain Hammons son of Ralph Hammons, and retired CEO of Hammons Products Company. The laborious process included stomping on the nuts to remove the hull, drying them in the sun, packing them in burlap bags, and then shipping them by rail to Virginia to be cracked.

It cost $16,000 to ship the nuts to Virginia, and Ralph Hammons realized he had an opportunity on his hands. According to Dwain, Ralph decided to take the chance to create his own processing facility, hopeful that it could be a good thing for southwest Missouri. Ralph Hammons went to a local bank to pursue financing for the purchase of the nut cracking machine. He was declined by the bank because he had no cattle to use as collateral. However, he was able to secure the money. The banker remembered that Hammons always paid his bills and loaned him the money himself.

A Family Business Rooted in Black Walnuts

During his high school years, Dwain Hammons would come to the plant in the summertime and help create new machines that would crack the nuts, with the goal of retaining as much of the nut meat as possible. Black walnut shells are notoriously difficult to crack. Dwain took over the business in 1954 after his dad had a severe heart attack, and he served as the president for 45 years.

After completing his degree at Missouri State, getting married, attending law school and practicing law for a few years in Kansas City, Brian Hammons returned to Stockton to take over for his father Dwain in 1999. “This was the best opportunity, and I had a sense of responsibility,” says Brian, current president and CEO of the company. “I needed to be and wanted to be part of this unique business.”

The Hammons family has found success handing down the traditions of running the company. “Leadership succession is critical,” says Brian. “You’ve got to have the ability for someone to come along and learn the ropes, learn the details, have the passion for the business, for the product, and for the community.”

Growing up outside of the daily demands of the company, Jacob Basecke, great-grandson of Ralph Hammons, was raised in Springfield. “I always had a great appreciation for the business,” says Basecke, the fourth generation working at Hammons Black Walnuts. After finishing his business degree at University of Missouri–Columbia, his uncle Brian presented him with the opportunity to get involved with the family business. “I started in 2014, and those first couple of months I shadowed in almost every department of the company, so that was a really good chance for me to get a better grasp of operations,” says Basecke, executive vice president of Hammons Black Walnuts.

Black Walnut Traditions

“In the early days, there were several black walnut shelling companies across the United States, and the reason we’re still here is we had wonderful employees that made it work,” says Dwain, noting their ability to sustain the unique set of challenges and experience success for nearly 80 years.

The Ozarks region is the epicenter of the black walnut industry and a place steeped in the tradition of hard work. “More black walnuts are grown, sourced and harvested in 417-land than anywhere else in the world,” says Basecke.

Whether it’s a cherished family recipe or the tradition of picking up black walnuts on an autumn day, many local families have warm memories of black walnuts. Generations have passed on the tradition that harvesting black walnuts can be a way to earn a living from a bit of hard work. Dwain loves it when people notice his Hammons Black Walnut shirt and stop him to share their story. “They tell me, ‘I bought my first baseball bat, or bicycle, by picking up black walnuts and selling them to the local huller,’” says Dwain. “They are so appreciative of the fact that they were able to pick up those nuts and get some money from doing it, and earning money for whatever they wanted when they were a child. It just makes me feel so good!”

“Outside of the Midwest, people don’t really know much about black walnuts and are fascinated by the scale of what we do,” says Basecke. Hammons Black Walnuts purchases millions of pounds of black walnuts each year from more than 200 hulling and buying locations in a 12-state area across the midwest and east-central United States. “We’re not only the main commercial supplier of black walnuts, but we’re one of the largest wild food suppliers in the country,” says Basecke.

Company Growth

American black walnuts, native to all midwestern states, are known for their distinct, rich, bold flavor. They are a sustainable wild food—watered by the rain and produced without chemicals or pesticides. Black walnuts also contain the highest amount of protein and antioxidants when compared to other tree nuts. Annually, 30 to 35% of bulk nut meat sales are for ice cream makers. “Black walnut ice cream has a rich history in the United States, and it was one of the original 31 flavors for Baskin Robbins,” says Basecke.

Black walnut sales have evolved over the years, as have people’s buying habits. The traditional baking nut category has seen reduced shelf space in grocery stores in many markets. However, more retailers merchandise both snacking and baking nuts in the produce section and along the store perimeter, reflecting store layout shifts and shopper habits and the increased use of nuts for snacking.

In January 2025, the Hammons Black Walnut company launched three new trail mix lines under the name Hike Performance Snacks. And in 2026 the company is adding new in-house packaging capabilities at the Stockton plant, to be able to support the snack mix lines and enhance current packaging.

The company’s primary revenue stream is nut meat, but the black walnut shell is another important line of business. The company produces six variations of black walnut shell, from course to fine grit, for use in other industries. In the auto industry, black walnut shell is used as a soft grit abrasive to clean engine parts and delicate metal surfaces without damaging them. The oil industry uses crushed shells as a lost circulation material to seal fractures in rock formations and reduce drilling fluid loss. They are also used as a filtration media in the oil and gas industry. Additionally black walnut shells were used to safely clean the exterior of the Statue of Liberty during restoration because of their gentle yet effective abrasive quality.

A relatively new market for black walnut shells is an organic alternative as infill in artificial turf sports fields. Soccer fields, baseball warning tracks, football fields and other recreational sports fields across the country are starting to add black walnut shells instead of crumb rubber on field surfaces. “The black walnut shell does really well because it’s durable, can be used multiple times, and helps reduce the field temperature by up to 15 to 20%,” says Basecke.

He adds that value-added segments will play a key role in the company’s future growth by helping them reach new audiences, diversify their product offerings and meet evolving consumer demands.

Incorporated in 1946 and approaching its 80th year in business, Hammons Black Walnuts has been able to survive by evolving with people’s tastes, responding to government regulations and changing with consumer habits, all while providing the same product over the years. “It is a unique business, a unique product and a very small industry,” says Brian. But the competitive landscape for the black walnut is still constant: “Squirrels! They get there first,” says Brian with a laugh.